Gesturing and Cognitive Affordances: The use of Gesturing to Facilitate Thinking Across English and Mandarin in Bilingual Speakers

| Name | Matriculation No |

|---|---|

| Daniel Tan Ren Jie | A0199712U |

| Ling Min Kang | A0201594J |

| Muhammad Excel Muslim | A0202923N |

Both speakers in our project are less fluent in Mandarin than English; consequently, the increased cognitive effort required to speak in Mandarin influences their gestures in Mandarin, making them slower and more distinct. We will analyse how these differences reveal cognitive processes and shape our thoughts in the following examples.

How poor Mandarin proficiency reveals the components of thoughts

Gestures can provide clues to the sequence in which speech is constructed. McNeill (2005) presents the different steps of gesture as different parts of the same thought and communication (p. 30), organised around the stroke (p. 33), however, the disfluency injected by poorer proficiency in one’s language breaks up one’s thoughts into visibly disparate sections that are visible through gesture.

EXAMPLE 1

Context: Min Kang provides directions for leaving Buona Vista MRT station.

Mandarin

Fig. 1. Prestroke pause prior to gesturing to the right with both hands, indicative of the transition between the decision to use a direction and the selection of a specific direction。

-搭到地铁站的出入口。出入口- 到出入口时,你要,ah,转 [pause, before pointing right] 右.

-take (the escalator) until you reach the exit. At the exit- when you reach the exit, you need to, ah, turn [pause, before pointing right] right.

In Example 1, the pause prior to pointing right seems to indicate that the decision to use a direction precedes and is separate from the decision to use a specific direction, along with the process of how to verbalise this direction in Mandarin. The gesture and verbal indecision align with each other in the prestroke pause where the hand is facing upward, and both describe the specific direction together after choosing a specific direction (Fig. 1).

EXAMPLE 2

Context: Min Kang provides instructions on how to reach Fine Foods from Cinnamon College.

Fig. 2. Pause between the uncommitted gesture (half bent right hand) and fully committed gesture (fully bent right hand), indicating the transition between picking a direction and specifying the aspect used to carry out the direction.

Um, 你。。。[pause] 继续往 [short pause] 右- 靠右边的那条行人路。

Um, you… [pause] continue towards [short pause] right- keep right1 along the pedestrian walkway on the right.

In Example 2, the speaker has decided on a direction, but not an aspect. He initially hazards the phrase “turn right”, and initiates a gesture for turning left (right hand half-bent pointing left; Fig. 2). Upon changing the expression from “turn right” to “keep right”, he re-initiates both the speech and the gesture components of the dialogue, opting for a more committed gesture (pointing the whole right hand left; Fig. 2). While both instances of dialogue used the direction right, the descriptive aspects were different (往 [“head”] vs 靠 [“keep”]), suggesting that the concept “rightwards direction” came before the decision of choosing how the movement in the rightwards direction should be carried out.

Furthermore, while the verbalisation of the phrase was wrong throughout Example 2 (“右” [you4] translates to “right”), the gestures consistently reflected the correct direction the speaker wanted the interlocutor to head towards (leftwards; see Fig. 2), highlighting how gesture is able to provide the correct semantic meaning of what the speaker is attempting to convey, even if he verbalises it wrongly.

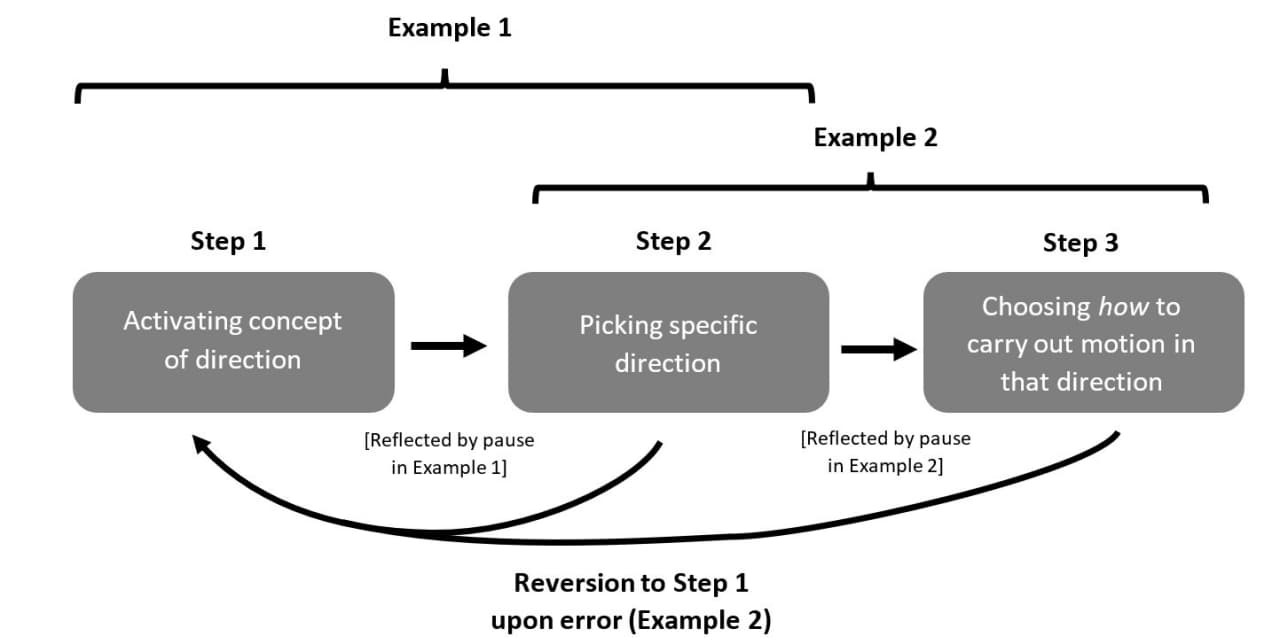

Fig 3.The breaking down of thoughts into their various component steps as revealed when verbalising thoughts in a language with lower proficiency (Mandarin), and how these components are illustrated through gesturing in Mandarin.

These examples suggest that ideas are not generated as a complete whole, but rather constructed as broad concepts first (Step 1 in Fig. 3), with specific details being decided on afterward (Steps 2 and 3, Fig. 3). In these examples, the steps appear to be 1) choose the concept of direction, 2) decide on a specific direction, and 3) decide on the aspect of the movement. When the idea is broken up due to poor language proficiency, its corresponding gestures are also broken up into separate events matching their respective thoughts. However, as illustrated in Example 2, when an idea is corrected, we restart the verbalisation and gesturing for the entire idea, rather than just backtracking one step, suggesting that the components that comprise thoughts are generated in a closely-linked way and cannot be easily separated cognitively.

Gesturing in Mandarin as wideware to facilitate speaking in Mandarin

EXAMPLE 3

Context: Min Kang is explaining the procedure needed to enter Fine Foods in Mandarin and in English.

Mandarin

Fig. 4. Two-handed pointing gesture referencing the self and the imaginary other, illustrating the metaphorical transfer of information to the uncle described in the Mandarin description.

你进了熟食中心后 [gestures both hands],你需要让一位, er [waves both hands], 先生看你的手机 [gestures with right hand],确保 [gestures with right hand] 你有把你的,er [gestures right hand], 体温跟,你的- 是否有没有,er [both hands gestures outwards], 生病的状况 [both hands point towards self] 告诉他 [both hands gestures outwards],确保你没有生病 [both hands gestures downwards]。然后,你进- 他才会让你进 [both hands point towards self],那个,熟食中心 [both hands gestures outwards]。

After you enter the food court [gestures both hands], you need to let a [waves both hands], er, man look at your phone first [gestures with right hand], to ensure [gestures with right hand] that you have your, er [gestures right hand], temperature and, your-, er [both hands gestures outwards], health declaration status [both hands point towards self] declared to him [both hands gestures outwards], (to) ensure that you are not sick [both hands gestures downwards]. Then, you enter- he will then let you [both hands point towards self] enter the food court [both hands gestures outwards].

English

Fig. 5. The use of the task-swiping gesture, co-timed with Min Kang’s verbalisation and listing of tasks.

Talk to the uncle, show him your [swipe gesture] uNivUS app and your declaration [swipe gesture], and then show that you’ve taken [swipe gesture] your temperature.

In Example 3, The “swiping” gesture that Min Kang uses when speaking in English (Fig. 4) mimics the “swiping” action used to close applications on handheld devices, suggesting that Min Kang cognizes and structures the tasks that he has yet to give Daniel by spatially representing them. With each swipe, he is “closing” each task (showing the uncle the application, then the declaration) sequentially, as if they were items on a to-do list. Furthermore, using this gesture also signals to Daniel that, like a list of applications, there is also a long list of actions to be completed.

Interestingly, both the sentences and gestures used when Min Kang is speaking Mandarin are longer and more descriptive than those in English (Examples 1 - 3). Moreover, when describing the scene in Mandarin, Min Kang’s gestures change completely: rather than the swiping gesture (Fig. 4), he constantly gestures at himself using both hands before pointing to an imaginary other (Fig. 5). As these gestures are co-timed to each clause, they convey the idea that “information” (e.g. temperature, health declaration status) is being metaphorically transferred to the uncle one at a time.

Examining the different gestures that Min Kang employs when speaking in English and Mandarin suggests that they may be influenced by the different levels of cognitive effort he requires when speaking in the two languages 2, which is influenced by his proficiency across the two languages. In Mandarin, Min Kang uses slower and more articulate gestures that give him time to construct his speech and find the correct Mandarin words. Gesturing here is used as wideware - it “play(s) a functional role as part of an extended cognitive process” (original emphasis; Clark, 1998, p. 268) by providing a non-verbal cue to the interlocutor that Min Kang was still thinking and required more time to retrieve the correct Mandarin words before verbalising himself. Gesturing out the meaning of the Mandarin words in detail also emphasises the semantic meaning of the Mandarin words that Min Kang uses, allowing him to convey their meaning more effectively.

In contrast, as a native English speaker, Min Kang did not need to rely on gestures to generate English words. Hence, this set of gestures reflects Min Kang’s cognitive state, rather than merely facilitating his finding of the right words. As described previously, the use of the “swiping” gesture illustrates the way he visualises the discrete steps as tasks in a to-do list. This was not reflected when he spoke in Mandarin, as his relatively poorer Mandarin proficiency required more cognitive effort, preventing him from reaching this abstraction step.

Gesturing in English as wideware to facilitate speaking in Mandarin

EXAMPLE 4

Context: Daniel is explaining what to do once inside of Kent Ridge NTUC, first in Mandarin, then in English.

Mandarin

Fig. 6. The use of the picking-up gesture, which is co-timed with the Mandarin phrase ”拿了“ (roughly translates to “pick up” in English).

你拿了猪肉后 [picking up gesture], 就可以买其他东西。

Once you pick up the pork [picking up gesture], you can go ahead and buy other stuff.

English

You can pick up your pork [PUOH gesture with both hands], and buy the rest of the ingredients [PUOH gesture with obth hands].

In Example 4, the “picking up gesture” (Fig. 6) employed by Daniel when saying “拿了猪肉” (lit. take the pork) initially appears to be pantomiming removing a packet of pork from a freezer, rather than influenced by the Mandarin words, since the gesture displays an “upwards” motion not encoded in Mandarin (the Mandarin words for “up” [上, shang4] and “rise” [起, qi3] are absent from the phrase3).

Further analysis of Daniel’s English verbalisation of the scene suggests that the gesture is influenced by the English translation he employs, rather than a pantomime. As Daniel uses “pick up your pork” to describe the same scene, the upwards gesture possibly reflects the “up” in the English translation “pick up”, even though he is speaking in Mandarin. There may be several reasons for this: firstly, basing his gestures off the English translation while he is speaking Mandarin helps the interlocutor to pin down the specific English translation of the Mandarin phrase he is using (i.e. “pick up the pork”, as opposed to “take the pork”) by incorporating the characteristic part of the English translation (“up”) into the gesture itself (upwards motion).

Additionally, understanding why these gestures are influenced by their English translations also helps us understand how gesturing reduces the cognitive effort required for Daniel to speak in Mandarin. As Mandarin is Daniel’s L2, he requires more cognitive effort to process his thoughts and convert them from English to Mandarin before verbalisation. Consequently, the gestures used when Daniel speaks Mandarin not only reflects his thoughts in English prior to their translation and verbalisation in Mandarin, but also serves to “aid (his) verbal formulation” (Kendon, 1997, p. 114) by functioning as wideware to organise his thoughts (Clark, 1998, p. 298; Alač, 2005): by gesturing the English phrase “pick up”, Daniel is able to use the physical action and visual perception of the gesture to facilitate his retrieval of the Mandarin equivalent of the phrase, reducing the cognitive effort he needs to speak Mandarin and facilitating his speaking of Mandarin.

Analysing the gestures Daniel uses when describing the scene in English supports this interpretation. When saying “pick up the pork” in English, Daniel uses two “palm up open hand” gestures (Fig. 7), rather than the “picking up” gesture used when speaking Mandarin. Since English is Daniel’s L1, he requires less cognitive effort to communicate in English compared to Mandarin. Consequently, his gestures no longer reflect the phrasing of his words, since he no longer needs to use gesturing to facilitate his thoughts. Instead, the gesture (Fig. 7) represents how he visualises the steps left to carry out: each gesture is co-timed with each action (picking up pork, buy the other ingredients), lending weight to the sequential completion of these tasks.

In Examples 3 and 4, both speakers use gestures as wideware to facilitate thinking when speaking Mandarin, since it is their L2 and requires more cognitive effort to articulate. However, they use gestures differently to facilitate thinking. Min Kang gestures what he is saying in Mandarin to nonverbally inform the interlocutor that he is thinking, to buy more time for him to articulate the next section of the dialogue. His gestures are also more deliberate and comprehensive in Mandarin compared to English to emphasise the semantic meanings of the Mandarin words he vocalises. In comparison, Daniel’s gestures are based on what he would have said in English. Rather than buying time for him to find the right words, Daniel’s gestures instead help him speak Mandarin by serving as external prompts to facilitate his retrieval of the corresponding Mandarin words. While Daniel’s gestures in Mandarin are similarly more detailed, they serve to convey the appropriate translation of Mandarin words he verbalises, rather than convey the semantic meaning of those words.

References :

Alač, M. (2005). Widening the Wideware: An Analysis of Multimodal Interaction in Scientific Practice. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, 27, 85-90.

Clark, A. (1998). Where Brain, Body, and World Collide. Daedalus, 127(2), 257-280.

Kendon, A. (1997). Gesture. Annual Review of Anthropology, 26, 109-128.

McNeill, D. (2005). How Gestures Carry Meaning. In D. McNeill, Gesture and Thought (pp. 22-62). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Footnotes :

-

Min Kang says right while pointing left; explained in a later paragraph. ↩

-

While the coordinate systems used in the Mandarin and English recordings were different (relative and cardinal respectively) due to the nature of the assignment, the examples used for analysis specifically drew from segments that did not cover any directions, preventing it from confounding our analysis. ↩

-

Alternative ways to express “pick up” in Mandarin are “拿上来” (na2 shang4 lai2) and “拿起来” (na2 qi3 lai2), both of which include the equivalent Mandarin character for the word “up” (上). ↩